Kaitlyn Stewart ’26 wasn’t expecting the opportunity to have a professional internship the summer after her freshman year.

Thanks to Marietta College’s recent partnership with Intel Corporation’s Appalachian Semiconductor Education and Technical (ASCENT) program, the Physics major was among five Marietta College students to receive a summer fellowship to pursue original research that encourages workforce development in the semiconductor industry.

Aaron Rohr ’24, Madeline Aszalos ’25, Aditya Shah ’25, Nick Haught ’26, and Stewart partnered with Marietta faculty to research various projects for six weeks.

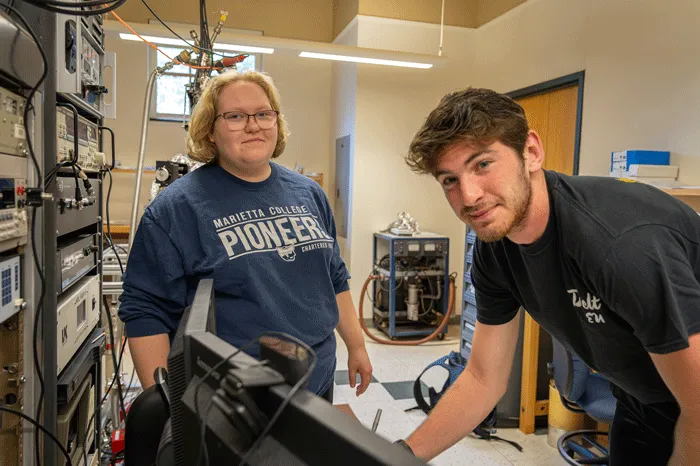

Stewart and Rohr worked with Dr. Dennis Kuhl, Rickey Professor of Physics, in the Physics Surface Lab.

“Our initial project is working in the ultra-high vacuum that we have and analyzing how different adsorbates affect the resistance of a thin gold film,” Stewart says. “This has been a very interesting experience, and because I’m just coming out of my freshman year, it was good to be able to learn alongside Aaron, who is more knowledgeable than I am.”

Rohr switched his major from Sports Medicine to Physics at the end of his sophomore year, so the hands-on research he has been able to receive gave him a solid background on what his career or his graduate work will entail.

“My main part is working on the ultra-vacuum chamber, which is helpful because in the fall, I’ll start my capstone work on the vacuum chamber,” Rohr says.

Funding for the fellowships comes from the Intel ®Semiconductor Education and Research Program for Ohio. Marietta is part of the ASCENT Ecosystem — a coalition of eight other Southeast Ohio institutions, colleges, and technical centers that is led by Ohio University. There are six additional institutions in other regions in Ohio leading semiconductor education and workforce programs as part of Intel’s Semiconductor Education and Research Program (SERP).

“Marietta College fills a different role than the other institutions in our partnership with the ASCENT program,” Kuhl says. “ASCENT has a major research university with Ohio University; it has Shawnee State University, so it has a regional public institution; it has as the technical schools and community colleges; and Marietta is the only liberal arts college in that collaboration.”

Kuhl says it’s important for Marietta to establish articulation agreements from the associate degree level (two-year college degree), and to the graduate level, which will help build a workforce pipeline that can be successful in the semiconductor industry in Ohio.

“Everyone’s heard of the term, ‘Silicon Valley,’ ” Kuhl says. “Right now, they’re talking about the ‘Silicon Heartland’ that’s being established in the state of Ohio.”

The educational component of ASCENT aims to prepare a workforce demand that’s coming to Ohio. Over the next five years, Intel plans to hire several thousand people with the new wafer fabs that it is building outside of Columbus, and about 70 percent of those employees will be technician-level employment — people with an associate degree — and 25 percent will be at the engineering level, such as process engineers, yield engineers and industrial engineers.

“We have majors in Chemistry, Physics, Applied Physics, Environmental Engineering and a newly approved major, Industrial Chemistry — all of those are appropriate backgrounds for process engineers and yield engineers,” Kuhl says. “So, there are great career opportunities in the near future. We’re trying to get that message out to prospective students that you can come to a place like Marietta and get a great liberal arts education and be well prepared to succeed in the semiconductor industry.”

In Kuhl’s lab, for example, Stewart and Rohr worked with growing metal thin films on silicon wafers to get some exposure to semiconductor silicon wafers. With the research and lab skillsets they develop, plus the communication and critical thinking skills they hone through their general education curriculum, Marietta College students will be well-prepared and highly sought out in the semiconductor and related industries.

Shah, a Computer Science and Physics major, and Aszalos worked with Dr. Joseph Smith, Assistant Professor of Physics, on two separate projects.

“Dr. Smith and I worked on finding the most precise machine learning models to analyze laser data, how lasers work,” Shah says. “When energy from the laser is transferred to the electrons and protons, we are trying to study that — how much energy is being transferred. We created a synthetic dataset to analyze those amounts and we created a synthetic dataset using previous scientific papers. With that, we created machine learning models.”

Shah says the fellowship was important to him in several ways.

“Financially, it allowed me to stay here at Marietta College, and it also provides me with experience because I plan to go to work right after my graduation,” Shah says. “I cannot afford graduate school so this fellowship helped me build a groundwork so maybe I will be able to work in AI (artificial intelligence).”

Aszalos, a Physics major with a minor in Mathematics and a Certificate in Leadership Studies, says the fellowship allowed her to expand her computer science knowledge.

“My project looks at simulations of lasers hitting targets, high-intensity lasers hitting targets,” Aszalos says. “Most of my job is to analyze the simulations, but Dr. Smith ran the simulations. So, what I’m mostly looking at is the maximum proton energy and the simulations, seeing how that differs across different dimensions — our simulations have 1D, 2D, and 3D simulations — and seeing how the 1D and 2D compare to the 3D, which is the real world, and what would happen.”

She anticipates going to graduate school and hopes to apply her skills to the medical field, though her studies will allow her a range of career options.

Haught is majoring in Computer Science and Applied Physics and, through the 3+2 program, will also graduate with a Mechanical Engineering degree from Washington University in St. Louis.

“In the Intel Internship, I conducted research on the functionalities of a pollution mass monitor (Teledyne T640),” Haught says. “Half of the duration of the internship was spent developing an application from scratch that interfaces with the pollution mass monitor. Using this application, I was able to analyze the incoming data and classify a room's cleanliness (according to the ISO classification standards for cleanrooms). Part of the work also consisted of documenting and presenting my progress.”

After completing his engineering requirements at Washington University in 2026, Haught plans to work in startups and venture capital firms.

“I think the Intel internship really opened my eyes to the semiconductor industry and just how massive and important it is to the modern world,” Haught says. “This internship impacted my career path by propelling me into the realm of software development and sparking my interest in semiconductors in general. Being able to create something from scratch that helps others communicate to a device was a rewarding experience.”